Nibelung treasure

March 2018 in Articles

Jerrold Northrop Moore on an unrecognized source for Wagner’s ‘Ring’

The aim of this note is to share what strikes me as an important discovery with those who can make better use of it than I am equipped to do. It concerns nothing less than what appears to be a plenary source for Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen music dramas, published seven years before he started work on Siegfrieds Tod.

The discovery began with my reading about the English artist Richard Dadd’s designs for wood engravings to illustrate one poem in The Book of British Ballads edited by S.C. Hall (London, Jeremiah How, 1842). The account showed that this was an English response to a German wood-engraved Nibelungenlied. Indeed, the dedication of A Second Series of British Ballads (How, 1844) reads: ‘To His Majesty Louis, King of Bavaria, whose munificent patronage of the arts has elevated the position and character of his country, secured his own imperishable renown, advanced the universal cause of civilization, and given an example and a stimulus to the other sovereigns of Europe, this volume, suggested by the works of German artists, is dedicated by his humble servant, the editor.’ The German royal dedicatee was the grandfather of Wagner’s young patron, Ludwig II.

Both frontispiece and title page of the book which stirred such international admiration are dated 1840. In fact, a publisher’s note dated 31 May 1841 makes clear that its production had been held up by the inability of the two commissioned artists to complete their designs on time. The publishers then brought in two further artists. One was the young Alfred Rethel, later recognized as the most distinguished German wood engraver of the 19th century. The publishers were the brothers Otto and Georg Wigand of Leipzig. They would go on to publish several of Wagner’s prose works. To print their illustrated Nibelungenlied, they hired the firm of Breitkopf and Härtel, who went on to engrave much of Wagner’s music.

The verse translation the Wigands published had been made by Wagner’s brother-in-law Gotthard Oswald Marbach (1810-90). In 1836 Marbach had married Wagner’s beloved eldest sister Rosalie, whose career as a successful actress had focused the interest of her teenaged younger brother on the theatre and its possibilities. Although Rosalie died in childbirth in 1837, he must have known of her widower’s celebrated book.

My copy contains a subscribers’ list running to 1,800 names of men and women from Dublin to Moscow and from Stockholm to Naples. It includes a fair proportion of the crowned heads of Europe and their heirs apparent. The London contingent alone runs to 150 names, headed by the Dowager Queen Adelaide (widow of King William IV) and Queen Victoria’s mother the Duchess of Kent. Most of the best British publishers from John Murray downwards are subscribers, together with a long list of literary lights including Charles Dickens, Captain Frederick Marryat, Richard Monckton Milnes, Thomas Moore, James Morier, Henry Crabb Robinson and W.M. Thackeray. The artist John Sell Cotman subscribes, together with the art historians Charles Eastlake and Anna Jameson, and Dean Liddell of Christ Church, Oxford, the father of Lewis Carroll’s Alice.

Prominent among German subscribers is Wagner’s greatest vocal inspiration, the celebrated contralto Wilhelmine Schröder Devrient. Schumann’s old teacher the Zwickau organist Kuntsch is here, together with Schumann’s dedicatees Abegg and Serre auf Marxen. More than one Mendelssohn subscribes. Metternich, two Bismarcks and two von Kleists appear, alongside names famous or infamous to later generations: Alexander von Humboldt, Prince Radziwill, von Richthofen, Jung, Bethmann-Hollweg, Strauss, Schnitzler, Ribbentrop, Göring. Viennese subscribers include the high court justice Johann Baptist Bach and the surgeon Carl Schubert.

Wagners abound from across Austria and Germany. Richard, penuriously at work on Der fliegende Holländer in Paris, would have been in no position to subscribe to his brother-in-law’s translation of this German epic in its expensive illustrated quarto. But many of its Paris subscribers were German, and one copy was destined for the French Royal Library.

Such was its success that the Wigands in Leipzig determined to bring out a separate edition of the Hohenems manuscript from which Marbach worked, Der Nibelunge Lied, in identical format with all the illustrations (1841).

More than a quarter of a century later, in sight of finishing Siegfried in Switzerland, Wagner wrote to Marbach on 9 April 1869 (Morgan Library, New York), asking for a copy of his brother-in-law’s Nibelungenlied for his library at Tribschen. There he plans to assemble portraits of kindred spirits—Mozart and Beethoven, Goethe and Schiller. Meanwhile, thanks to King Ludwig II, Rheingold is soon to be produced in Munich.

Yet nine years earlier, in 1860, the surviving Leipzig publishing brother Otto Wigand had brought out a reduced-format Die Nibelungen. In Prosa übersetzt, eingeleitet und erläutert von Dr Johannes Scherr. Scherr (1817-86) was a revolutionary as well known or notorious as Wagner himself, and the author of philosophical works still read in Germany. Here the emphasis—with translator’s foreword, 20-page introduction and 15 pages of scholarly footnotes—is more literary and historical. Scherr’s introduction of 1860 observes:

‘The German public is now beginning to understand that this ancient text could be a nucleus of national strength, and a modern prose version will help to disseminate the story amongst those who are not inclined to read archaic verse.’ (Translation by my friend Georg Kastl, who goes on to observe that ‘Scherr had examined all earlier editions of the 19th century before producing this highly readable one, which combines the tone of a medieval chivalric novel with realist narrative techniques.’)

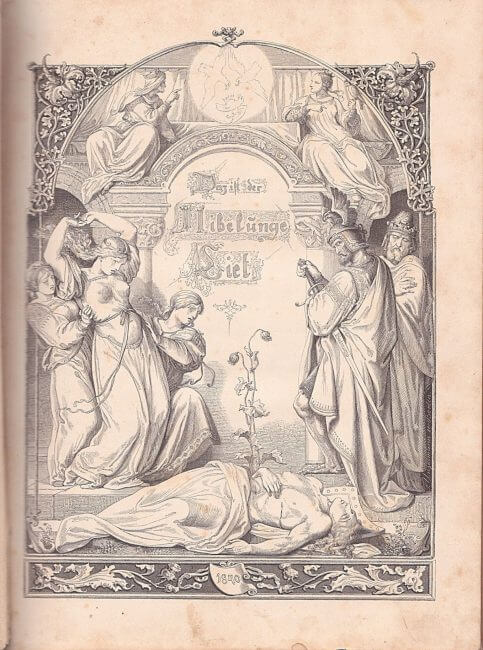

All of the old engravings are still included (some rendered borderless by the smaller format)—except for Siegfrieds Tod, prominently dated ‘1840’. Yet that could already have given Wagner its suggestion to start his work on the Nibelung music dramas. For the engraving shows the dead Siegfried with a Jesse tree growing from his loins. This reaches towards the three Norns on one side, on the other to Hagen (sheathing his sword) and Gunther.

The book in which I found my first reference to the wood-engraved ‘Nibelungenlied’ is Nicholas Tromans’s ‘Richard Dadd: the artist and the asylum’ (Tate Publishing, 2001), p. 16. Roger Dubois identified that edition’s verse translator as Wagner’s brother-in-law. Finally, Georg Kastl and my old friend Andrew McGeachin at Henry Sotheran’s bookshop managed the far from easy task of finding me copies of all three of these now very uncommon books.